When the operator of the nation’s tallest dam applied for a new federal permit in 2005, few expected the process to drag on for more than a decade.

It’s still not done.

California’s Oroville Dam is among a dozen major hydroelectric projects that have been waiting over 10 years to receive a long-term permit from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. The sluggish process is fueling uncertainty about the future of a key source of clean power that has bipartisan support in Congress — but that faces new challenges as the climate warms.

“We’ve been in this patient mode for 17 years, waiting for the license issuance. We’re kind of just tired of it, to be frank,” said David Pittman, the mayor of Oroville, a small city in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains located directly downstream of the dam.

Over 160 hydropower projects across the United States will see their longstanding federal permits, known as licenses, expire between this year and the end of 2027. That’s on top of the dozens of projects with licenses that have already lapsed but have not yet received a new one from FERC.

While dams with expired licenses still operate through temporary approvals, the long and expensive relicensing process could lead some dam owners to stop operating projects later this decade, according to industry watchers. The trend also may have broad implications for the electric resource mix, carbon emissions and the reliability of the power grid, particularly in the western United States.

Hydropower contributed just over 6 percent of electric power in the country last year. Compared to solar, wind and some fossil fuel plants, the resource has the ability to quickly and reliably ramp up when demand for power spikes, helping to stabilize the grid, said Caitlin Grady, an assistant professor in engineering management and systems engineering at George Washington University.

“Some hydropower turbines can actually be turned on even faster than natural gas peaking plants,” Grady said in an email. “But [FERC] license operations rules might constrain a certain plant’s ability to serve as a peaker plant.”

While hydropower dams that exist today emit relatively few carbon emissions when operating, dam building in the 20th century disrupted ecosystems, flooded tribal lands and altered natural landscapes. Obtaining a new, long-term hydropower license, which lasts 30 to 50 years, from FERC is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to modify how projects operate.

The effort can also be used to reduce the environmental impacts of dams, many of which were built prior to the passage of the Clean Water Act and other environmental laws.

Yet when the relicensing process takes many years, potential improvements to dams get delayed, frustrating dam operators, environmental groups and nearby communities alike.

“You’re not going to invest tens of millions of dollars in upgrades in a facility if you don’t have a longer-term license,” said Malcolm Woolf, CEO of the National Hydropower Association, an industry trade group.

The issue is not lost on members of Congress.

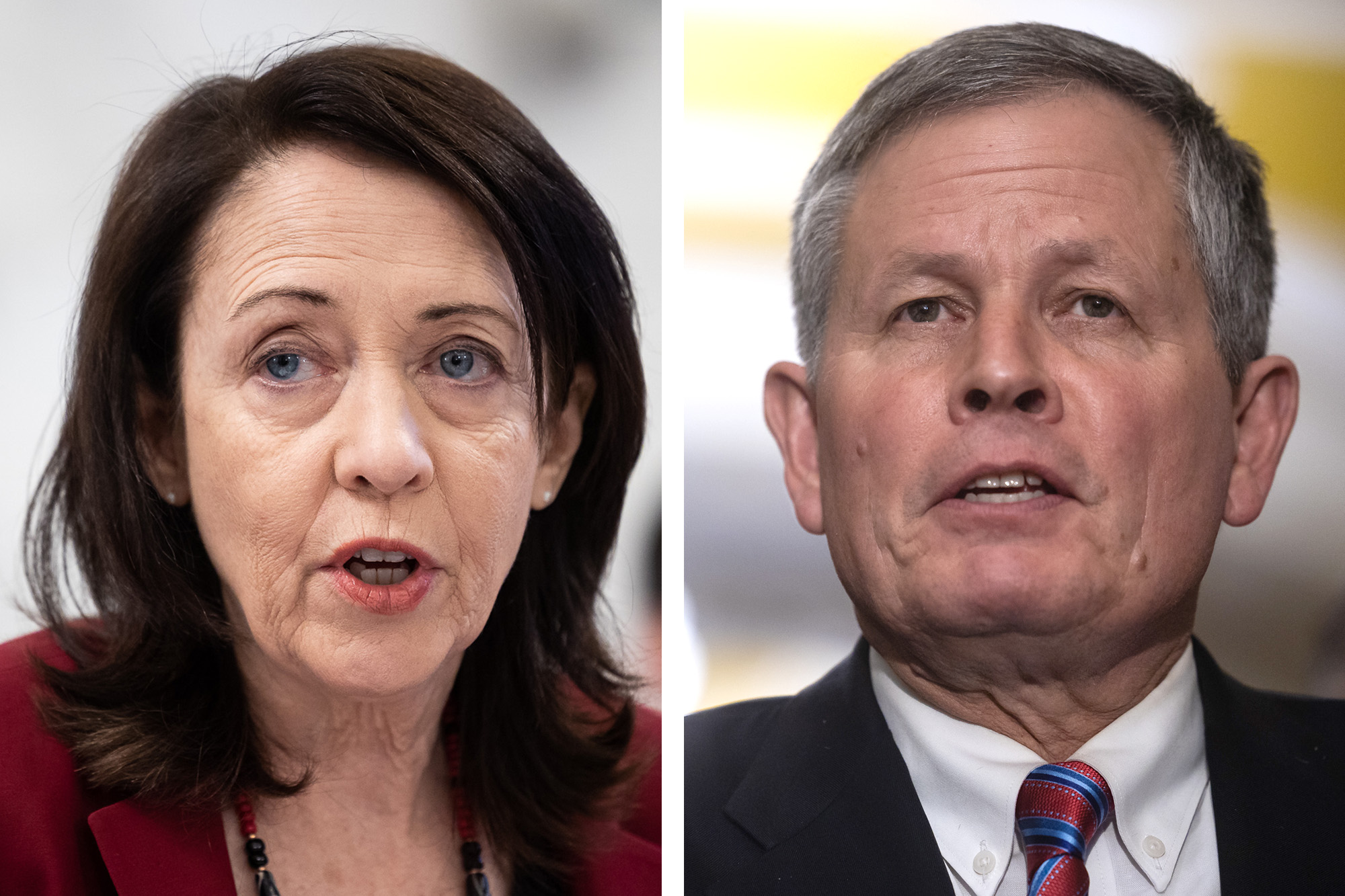

On Thursday, the Senate Energy Committee is scheduled to consider legislation from Sen. Steve Daines (R-Mont.) and Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.) that aims to reduce the permitting time for new and existing hydropower projects, including those with relatively modest environmental impacts. The bill has support from the hydropower industry, environmental groups and former FERC commissioners. It could be the most significant hydropower legislation in decades.

Most power-generating dams were built for flood control and other purposes in addition to electric power. Often, a number of state and federal agencies participate in relicensing. How dams impact fish species, recreational activities and water quality, among other issues, must be taken into account.

In some cases, however, projects appear to have met all requirements for a new license, yet still wait years to get one from FERC. That’s the situation for Oroville, said Ted Craddock, deputy director of the State Water Project at the California Department of Water Resources, which operates the dam.

Back in 2006, the state agency reached a settlement agreement with local governments, citizens’ groups, tribes and other parties. The department agreed to invest about $500 million in upgrades at Oroville, including some measures intended to benefit an endangered species of salmon, Craddock said. But nothing can be implemented until FERC grants a new license.

FERC declined requests to discuss Oroville or other long-pending permits or to point to specific issues holding up Oroville’s license. The agency cited its policy of not commenting on pending matters. The agency has estimated that relicensing typically takes about five years.

At this point, FERC has had “everything they would need” to approve Oroville’s pending license since late 2016, according to Craddock.

“We are anxiously awaiting the new license to be issued and want to see it so we can implement all the things that were committed to as part of the settlement agreement,” he said.

Beyond Oroville

Built in 1968, the Oroville Dam can produce enough electricity to power more than 700,000 homes when water levels are at their highest. It is also a key component of California’s State Water Project, which delivers drinking water for millions of people in the Golden State.

Oroville received international attention when the 770-foot-tall dam nearly failed following heavy rains in February 2017. The project’s spillway — which allows for the controlled release of water from Lake Oroville — partially collapsed, spurring fears of an uncontrolled, life-threatening flood. Over 180,000 people living downstream were ordered to evacuate.

Although severely damaged, the dam ultimately avoided full-blown collapse, and the state Department of Water Resources built a new spillway in 2018. The agency says the project is now safe and structurally sound.

While Oroville’s near-failure is unusual for a dam in the United States, its drawn-out relicensing process is not — especially in California and the West.

“It’s beyond just Oroville,” said Dave Steindorf, a California hydropower specialist at American Whitewater, a river conservation nonprofit.

American Whitewater has long been at odds with the hydropower industry because of dams’ effects on river access and ecosystems. Yet Steindorf agrees with industry on the need to reform hydropower licensing, and supports the pending bill in the Senate.

Another project Steindorf has tracked is the Upper North Fork Feather River Hydroelectric Project, which is about 90 miles north of Oroville. Operated by Pacific Gas and Electric Co. (PG&E), the project can generate enough electricity to power up to 300,000 homes. Its FERC license expired in 2004.

One reason why relicensing Upper North Fork initially dragged on is California’s water quality certification. The state-level certification is required under the Clean Water Act before FERC can approve a license, and California did not issue one until 2020 — 15 years after an environmental impact statement was issued. Although the state certification was the last outstanding issue for Upper North Fork, FERC still hasn’t approved a new license.

Similar to the case with Oroville, dam owner PG&E is supposed to make recreational and environmental improvements in the area surrounding the Upper North Fork project under the terms of a settlement agreement, Steindorf said. But those initiatives won’t get done until a new license has been granted.

“It’s at the head of the Feather River system,” Steindorf said of the project. “There’s a whole bunch of stuff in that settlement agreement — things that are not happening and have been languishing for almost 20 years now.”

Regarding Oroville’s license, an ongoing dispute with Butte County, Calif., could be part of the holdup, said Chris Shutes, executive director of the California Sportfishing Protection Alliance. The conservation nonprofit has also been critical of the impacts of dams on rivers and fish.

Butte County, where the dam is located, has filed lawsuits over various issues pertaining to the project. Among other grievances, the county claims it has not been fairly compensated for the dam’s impacts.

“I think part of FERC’s calculus is, ‘We don’t want to give you a license if there’s ongoing litigation about the water quality certification,’” Shutes said. “My personal opinion is that’s more of an excuse for FERC to delay, rather than the reason for delay, but that’s a pattern that happens.”

The adequacy of the Oroville dam's new spillway could also be a behind-the-scenes factor.

Ron Stork, senior policy advocate at Friends of the River, said he remains concerned about whether the spillway is big enough to handle a “probable maximum flood,” the most severe flood considered possible in the area. The California-based river conservation group has called for stricter environmental mitigation measures at dams.

Stork had warned of the potential for the old spillway to collapse back in 2005. Still, he can’t say for sure whether that’s holding up the license because FERC classifies many communications with the California Department of Water Resources and other dam owners as critical energy infrastructure information, a security practice that began after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

That means those documents aren’t available in full for the public to see.

“One of the problems is that, fundamentally, these discussions between FERC and particularly the [FERC] division of dam safety and inspections take place behind the scenes,” Stork said. “There’s no real public process.”

Celeste Miller, a spokesperson for FERC, said in a statement that interested parties “have numerous opportunities to provide the Commission with information, comments, and recommendations.”

Craddock, of the Department of Water Resources, said the Oroville spillway fixes are separate from relicensing and that FERC has endorsed the state agency’s repairs, which cost over $1 billion. The commission also required that an independent board of experts review the engineering and construction for the new spillway, he said.

“They do have ex parte rules, so they’re not able to respond to questions that we have in terms of when is the license going to be issued from a legal standpoint,” Craddock said.

Hydropower legislation

As projects wait for new licenses from FERC, lawmakers on Capitol Hill are considering major legislation that make making hydropower permitting more efficient.

How much the proposed changes could help speed up the relicensing of existing dams, however, is a matter of debate.

In addition to establishing a shorter licensing process for certain new hydropower facilities, the Senate bill from Daines and Cantwell would seek to improve engagement with tribes and encourage coordination among different agencies. Another piece of legislation geared toward speeding up licensing has been introduced in the House by Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Wash.) and is scheduled for a hearing before the House Energy and Commerce Committee on Wednesday.

Lawmakers backing changes to hydropower licensing say they could help bring industry regulations into the 21st century.

“This legislation is the culmination of years of discussion and compromise between a host of conservation groups, energy providers, Tribes, and local stakeholders,” Daines and Cantwell wrote in a letter to Senate Energy Chair Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) and ranking member John Barrasso (R-Wyo.) this month.

While the Senate bill has support from dam owners, conservation groups and a number of Republican and Democratic lawmakers, some larger challenges with the relicensing process still fall outside of its scope.

For example, the bipartisan bill mostly focuses on FERC, rather than other federal or state agencies, said Aaron Levine, a senior legal and regulatory analyst at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. For that reason, it would not necessarily speed up the pace at which some states issue water quality certifications, Levine said.

“It’s not some kind of holistic overall that’s going to reduce licensing times by two or two and a half years across the board,” Levine said.

The same Senate bill also leaves out the question of how dams should operate in a warmer world and as part of a future grid powered largely by renewable energy, said Grady of George Washington University. The proposed House bill includes some language on that issue, including declaring that U.S. hydropower should be preserved and expanded “to address a changing climate and improve environmental quality.”

Ideally, dam owners should be able to adjust their projects in response to changes in the energy resource mix as well as climate change, Grady said. But changing a dam’s power output in real-time can have other impacts, such as on the water temperature downstream, which may not be allowed under the relatively rigid licensing system that currently exists, she said.

Although FERC permits account for temperature and precipitation patterns in recent decades, Grady said, projects aren’t required to analyze future climate change impacts.

“If you’re talking about a hydropower dam trying to future plan for climate changes, that’s still pretty difficult to do in this structure of FERC licensing,” she said.

The impacts of extreme weather and storms on hydropower are particularly apparent in California, which aims to decarbonize its power supplies entirely by 2045. Hydropower supplied about 10 percent of the state's electricity in 2021.

In June 2022, the U.S. Energy Information Administration estimated that hydroelectric generation would decrease that summer in California because of the long-standing drought, leading to more reliance on natural gas. But by this past winter, heavy precipitation and extreme storms had helped replenish reservoirs, prompting concerns not about drought, but floods.

If California wants to further slash emissions, it would make sense for regulators to figure out how to best use existing hydropower — and prepare projects for climate change-fueled extreme weather, Grady said. Retaining dams like Oroville should also be a priority, she added.

That point is not lost on Pittman, the nonpartisan mayor of Oroville, who said he contacts FERC regularly for status updates on the dam’s pending license.

“Are we trying to push FERC?" he asked. "You bet."