PIKETON, Ohio — With the push of a few buttons, Biden administration officials and the CEO of nuclear fuel company Centrus Energy marked the first new domestically owned uranium enrichment production on U.S. soil in 70 years.

The opening of the company’s American Centrifuge plant here this month, with more than 100 union leaders, nuclear industry supporters and politicians looking on, was hailed as a milestone for the future of U.S. nuclear power that can help tackle climate change, bolster national security and create thousands of union jobs.

“This is a moment of pride and promise for the nation,” declared Centrus CEO Daniel Poneman, a former deputy secretary at the Department of Energy.. The technology could help the U.S., which invented uranium enrichment, recover its “lost nuclear independence,” he added.

Also at stake, Centrus and its supporters say, is the future of the U.S. industry, as the plant is the only facility licensed by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to produce what is known as high-assay low-enriched uranium, or HALEU. The fuel, which currently has a supply chain dominated by Russia, is expected to power the next generation of U.S. reactors.

But realizing Centrus’ vision lies not with the demonstration-scale project on display that day, but with building “thousands of additional machines” capable of producing tons of the nuclear fuel, Poneman said. And doing that won’t happen quickly and requires billions more in federal dollars — a point that nuclear industry critics say shouldn’t be lost.

Among the skeptics is Edwin Lyman of the Union of Concerned Scientists, who said the nuclear industry has a long history of over-promising and under-delivering. What some in Washington view as new momentum for nuclear as a climate solution, he sees as a public relations campaign to tap into “massive amounts of government funding.”

“The fundamentals aren't really there,” Lyman said in an interview. “They're trying to create a demand out of whole cloth. And I don't think that's going to end well.”

Even so, many have high hopes for a nuclear revival. More than 20 U.S. companies are developing advanced nuclear reactors, many of which will require HALEU.

Natural uranium is composed of less than 1 percent of U235, the isotope capable of sustaining a nuclear reaction, and low-enriched uranium has a concentration of almost 5 percent. HALEU is enriched to almost 20 percent U235, still well below the 90 percent level of weapons-grade uranium but dense enough in energy that just 3 tablespoons equals a lifetime worth of power for American consumers.

The Department of Energy estimates that more than 40 metric tons of the fuel will be needed before the end of the decade, with additional amounts required each year, to deploy a new fleet of reactors to help achieve President Joe Biden’s goal of 100 percent carbon-free electricity by 2035.

But before Centrus, which is headquartered in Bethesda, Md., can scale up, it needs customers. Until then, company executives can only ponder what might be.

“As we move into expansion, the question is: What is that expansion?” said Jeff Cooper, Centrus’ engineering director and a 20-year company veteran, who briefed visitors on the potential of the American Centrifuge plant.

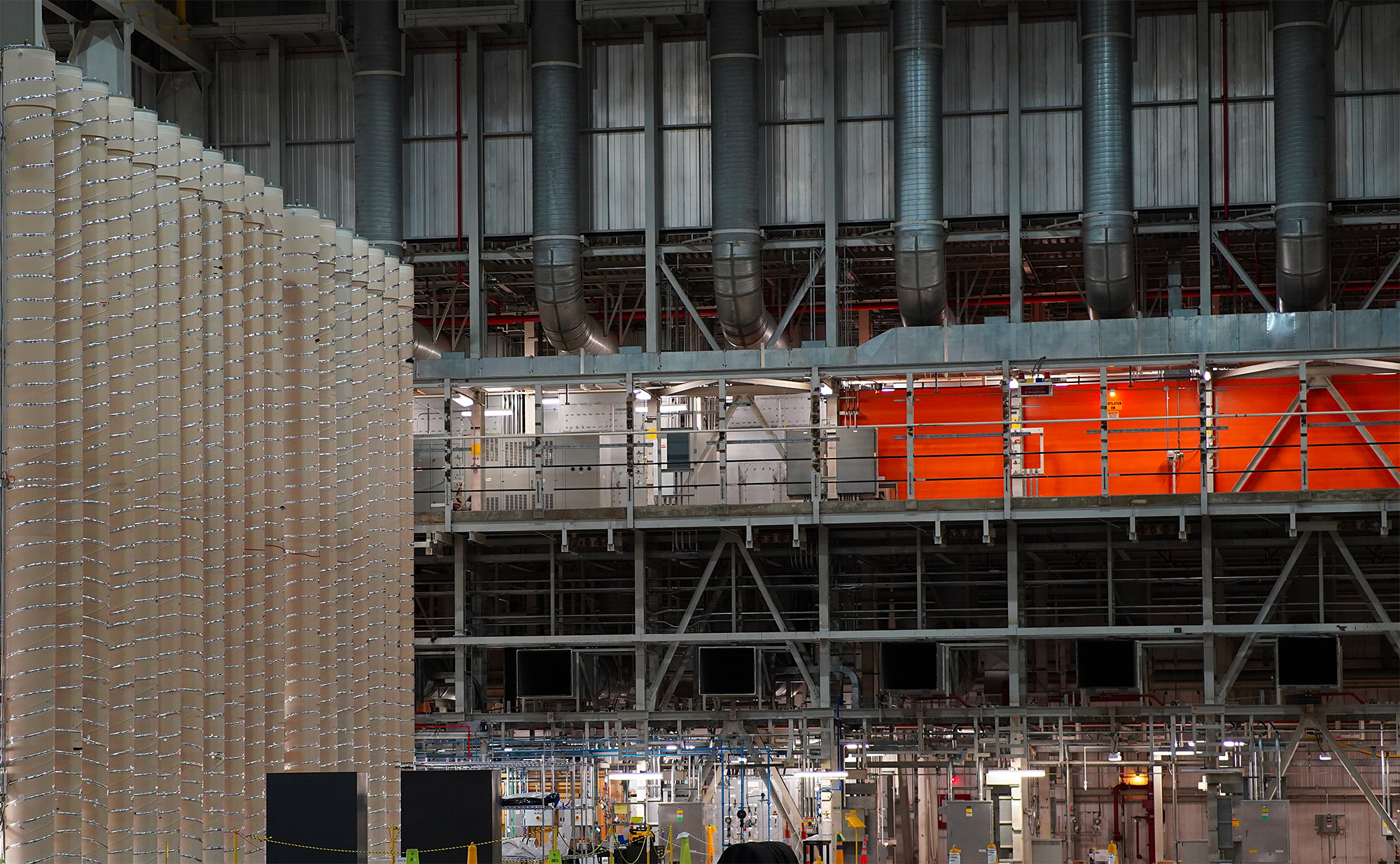

The plant, equal in size to the Pentagon, is part of a much larger complex known as the Portsmouth Gaseous Diffusion Plant, a site chosen in the early 1950s for uranium enrichment, initially to support the nation’s nuclear weapons program.

It’s inside cavernous Building X-3001, with its steel skeleton and concrete floors, where Centrus aspires to expand to produce HALEU for a fleet of advanced reactors as well as produce low-enriched uranium that’s used as a feedstock. Another building of equal size lies just beyond one of the walls.

Inside the building, maintained at a tropical 90 degrees Fahrenheit, is a row of 16 slender white tubes, each four stories tall — a “cascade” of centrifuges that have begun to produce the first 20 kilograms of HALEU.

A contract with DOE calls for Centrus to up that volume to 900 kilograms a year to help support new reactor demonstrations.

Bill Gates, Russia and the climate law

Today, commercial volumes of HALEU are produced exclusively by state-owned foreign governments. Russia’s dominance in the industry was troubling for U.S. officials even before Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

TerraPower, the Bill Gates-backed advanced nuclear developer, said in December that the start date for its Natrium reactor in southwestern Wyoming has been pushed back from 2028 because of lack of fuel availability. The company initially planned to source Russian fuel, but it scrapped those plans after the invasion.

Researchers and the nuclear industry say jump-starting a domestic supply chain is a classic chicken-and-egg dilemma.

Committing billions of dollars to a fleet of new reactors relies, among other things, on a dependable supply of fuel, but fuel supplier Centrus, which has memorandums of understanding (MOUs) with advanced reactor companies such as TerraPower and Oklo, needs commitments from customers.

“Suppliers don't have that clear market signal yet for what the timing and volume of demand will look like, so they don't [have] the ability to make an investment decision,” Nima Ashkeboussi, senior director of fuel and radiation safety at the Nuclear Energy Institute, said in an interview. “So, it's kind of a lot of wait and see.”

Under the MOU with Santa Clara, Calif.-based Oklo, for instance, fuel from the Centrus plant in Piketon would power two Oklo plants located nearby on another parcel of the former DOE Portsmouth Gaseous Diffusion Plant that would generate 30 megawatts of power and 50 MW of heat.

Long lead times on both fronts only complicate the dilemma and add urgency. According to Centrus, it will take 42 months after receiving an order to construct a commercial cascade of 120 centrifuges.

“You're talking about close to four years until you're getting meaningful production out of that facility,” Ashkeboussi said. “And you got to start that today. When those [new] reactors are ready to go, we want to make sure that they have fuel.”

Alan Ahn, a senior fellow at think tank Third Way, is among those who think the only real solution is the federal government, which could step in as an intermediary, a buyer of the initial commercial production of HALEU, thus providing market certainty to Centrus and companies looking to deploy next-generation reactors.

But $700 million slotted for HALEU production in the Inflation Reduction Act won’t be close to enough. Third Way estimates that $2 billion to $3.5 billion in upfront appropriations are needed to secure multiyear contracts with uranium enrichers and to spur investments in new capacity.

“You really need the federal government to come in and play sort of that role as initial off-taker, or first buyer, of this material,” Ahn said.

The source of potential funding isn’t clear yet, nor is how soon Congress might act amid the chaos over House leadership and Israel. There is some bipartisan support on Capitol Hill for boosting domestic production of HALEU, including through a bill introduced last month from Rep. Bob Latta (R-Ohio) and Assistant Democratic Leader Jim Clyburn of South Carolina.

DOE history

This isn’t the first time that Centrus or its predecessor, U.S. Enrichment Corp. (USEC), has needed funding to jump-start domestic nuclear fuel production. The company, in fact, traces its roots back to when it was spun off by the government during the Reagan administration.

In 2009, DOE denied a $2 billion loan guarantee for a uranium enrichment plant in Piketon to produce nuclear fuel, citing “technical” problems. Debt-ridden USEC would seek Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection just a few years later.

The company emerged from bankruptcy as Centrus. But after years of jockeying to salvage the American Centrifuge project in Piketon, the Obama administration walked away from it in 2015 — a decision blasted by Ohio’s congressional delegation.

But a lot’s changed since then, Ahn said, including a momentum around the role of nuclear power in helping the nation meet its climate goals both in the U.S. and globally.

Politically, too, there’s more support for nuclear energy among Democrats in Congress, he said, as evidenced this summer by the 96-3 passage of Sen. John Barrasso’s (R) Nuclear Fuel Security Act in the Senate. The amendment, part of the 2024 defense bill, directs DOE to prioritize increasing domestic production of enriched uranium for existing reactors and to accelerate availability of HALEU for advanced reactors.

Finally, there’s the issue of national security, which has only grown larger in the past year and a half.

Still, the nuclear industry also faces the same criticisms and concerns that have dogged it for decades, including a history of delays and cost overruns, unmet promises that have plagued the nuclear power industry from its inception to the most recent reactor built in the U.S. — Southern Co.’s Plant Vogtle in Georgia.

Lyman of UCS said the new breed of reactors that are less than 300 MW that will require a new “exotic” fuel don’t solve the nuclear industry’s cost issues. While they have lower capital costs than large plants and are therefore more affordable for utilities, they are not more economical, he said.

The bottom line, Lyman said, is that it will take more than just an initial investment by the federal government to get a new nuclear fuel cycle up and running to the point it will attract enough private capital to be self-sustaining.

“It would have to be a lengthy, sustained and consistent effort,” he said.

But for Poneman, the government partnerships that have underpinned every enrichment facility ever built “can underpin this one as well.”

“When the industry sees government stepping up, they will step up and provide the order book that will sustain the business and allow us to raise private capital to match the public investment,” he said.

Correction: A previous version of this story misidentified Daniel Poneman’s title and misstated how long it has been since a uranium enrichment plant was built in the U.S..